Workplace conflicts are a natural part of organisations. Wherever people interact, there is at least potential for conflict. The longer people interact, and the more people they interact with, the higher the chance of some conflict arising. Indeed, sometimes we don’t even need other people to have a conflict with – a conflict with ourselves isn’t that rare after all.

Since conflicts won’t be going away anytime soon, we would like to support you to better 1) understand, 2) resolve, and 3) prevent conflict.

But before we dive into those three topics, let’s look at what we mean by conflict, and how to structure different kinds of conflict.

What do we mean by conflict?

There are many different definitions for conflicts, and reasonable people can disagree on which one fits best. For the purposes of this article, we will take conflicts to mean “a struggle that results when one individual’s concerns or needs are hurt by someone else; or are different from someone else’s needs or concerns”.

Crucially, this does not necessarily mean that you shout at each other to have a conflict. Conflicts can be resolved or dealt with entirely amicably. So, a conflict is not (at least for this article) defined by the way it is handled, but by the underlying situation.

Not all conflict is created equal

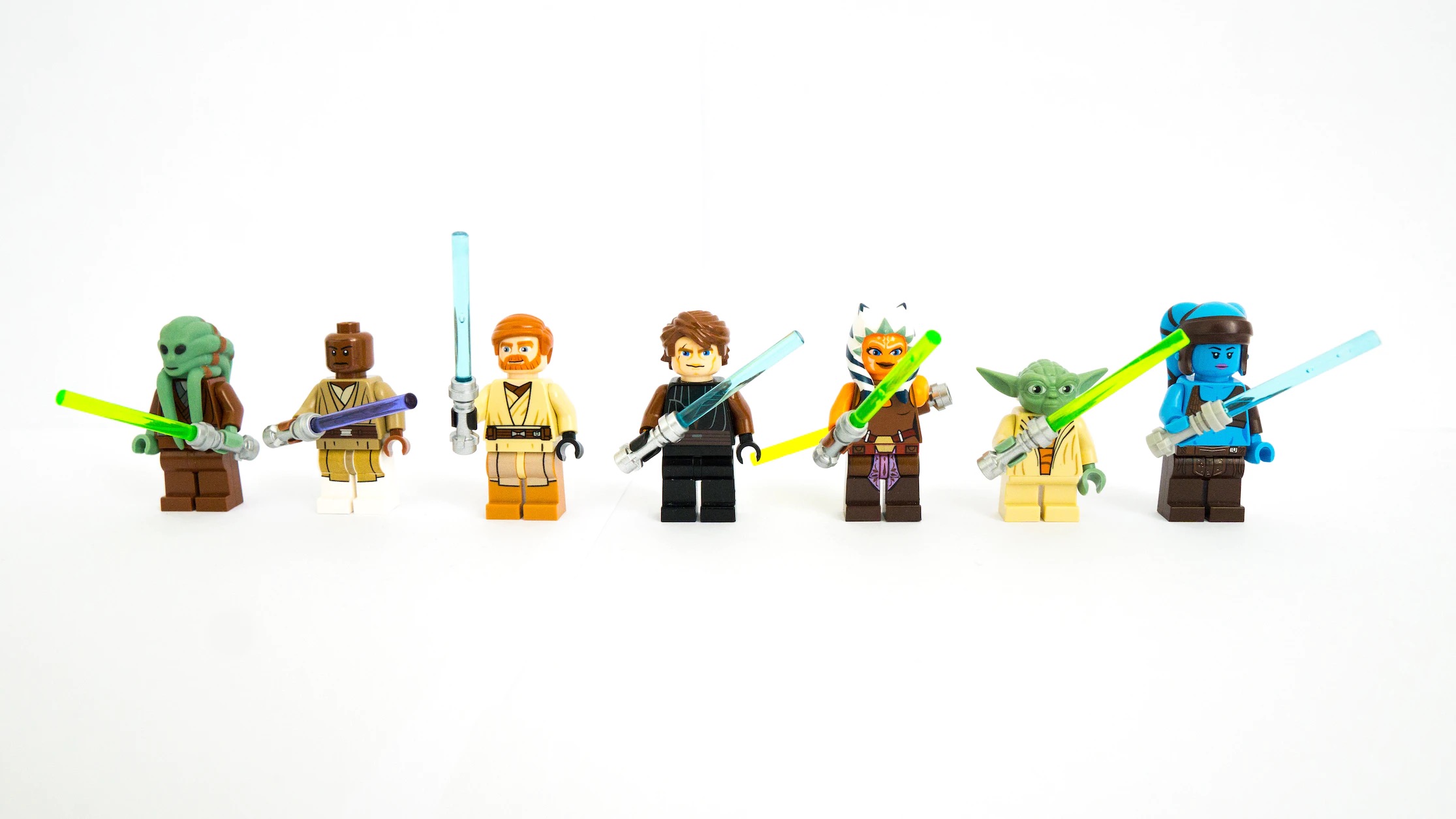

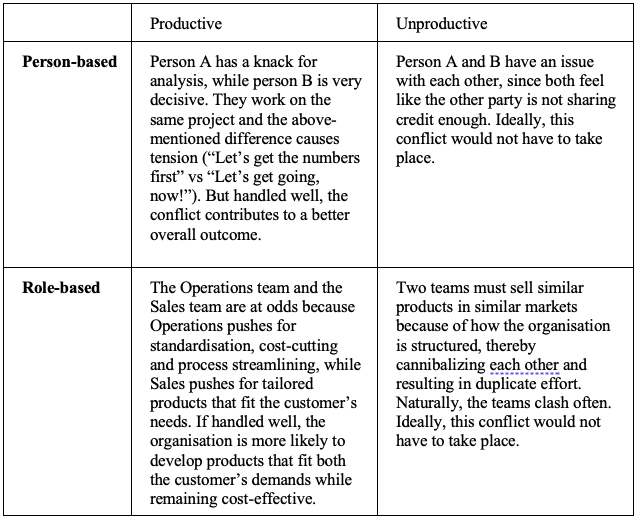

A helpful way to structure the topic of workplace conflicts is a simple 2×2 matrix. On one axis we have productive vs unproductive conflict, and on the other we have person-based vs position-based conflict.

A good question to check if your conflict is a (potentially) productive one is: “would we be more or less productive/innovative/efficient/etc. if we did not have this tension?”

Conflicts are productive if having them helps us better attain organisational objectives. But if preventing a conflict helps us better attain organisational objectives, it would be an unproductive conflict.

Person-based conflicts are those that arise from interpersonal differences. Position-based conflicts are those that arise from interactions between roles/positions.

We have included some quick examples to make the distinctions more tangible.

Understanding conflicts: biases

As we have already seen above, we can distinguish between two sources for conflict: persons and roles. This article will focus on person-based causes, starting with biases.

Our brain isn’t perfect. It has evolved to deal with a very complex environment using limited mental resources. So, it has developed short-cuts, rules of thumb and pattern recognition. The good news is these biases helped us survive for millions of years. The bad news is that these rules of thumb can make us inadvertently misjudge situations, other people and ourselves and thereby contribute to conflicts.

While biases are interesting and varied enough to warrant multiple articles just by themselves, we will focus on three biases in this context. 1) The fundamental attribution error and 2) the ego-centric bias and 3) ingroup-outgroup bias.

Understanding conflicts: fundamental attribution error

The fundamental attribution error describes our tendency to explain other people’s bad behaviour with who they are, while explaining our own bad behaviour because of the situation.

A quick example illustrates this quite nicely: imagine you’re driving in your car and someone else is cutting you off. How do you explain this behaviour? The likely explanation will be some variety of “because that person is an idiot who shouldn’t be allowed behind the wheel of a car”.

Odds are, at some point you accidentally cut off someone else in traffic. How did you explain that behaviour? This is when we suddenly get creative: “I was in a hurry”, “I almost missed my exit”, “That car was impossible to see”, etc. In other words, there are plenty of explanations for this behaviour, but you being a bad driver is likely not of them.

The fundamental attribution error means we tend to see ourselves as well intentioned despite outward appearances, while not giving other people the same benefit of the doubt, or even actively accusing the other party of bad intentions. Ironically, the other person sees things the same way, only the other way around. Not necessarily the best set-up for a speed conflict resolution.

Understanding conflicts: ego-centric bias

The ego-centric bias describes our tendency to overestimate how many other people share our views, values, experiences, knowledge etc. This is not us saying that you are a bad person – after all, our society tends to view egocentrism as a bad thing – it is a result of the number of brains you have access to, which is exactly one: your own brain. So, when your brain makes judgments, it extrapolates based on the most complete set of data available, which is your own data.

So how does this lead to or exacerbate conflict? Think for example about how you would define “respect” in the workplace. Now try to estimate how many other people would define it the same way. Odds are, you overestimate that number.

Now, when we interact with someone who we feel is being disrespectful, we assume they understand “respect” in the same way, or at least very similarly to how we understand it. So, the explanation for their behaviour is that they want to be disrespectful or just don’t care enough despite knowing better. When really it may very well be the case that the other party simply has a different understanding of respect (which they probably assume we share, because no one is safe from the ego-centric bias).

Understanding conflicts: ingroup-outgroup bias

The ingroup-outgroup bias describes our tendency to be more generous and lenient towards those we perceive to be part of our group, while being harsher and more adversarial to those we perceive to be outside our group.

For a very quick example, consider basically any sports event ever. Whole groups of people, who are otherwise gentle and loving members of their community, suddenly shout at each other because they wear jerseys of different teams.

How grievous was that foul? That depends. Was someone on my team fouled? Then the referee should send of the fouling player immediately! If my team did the fouling, then it was definitely justified and at best a light push.

In a workplace context, similar things can happen with teams, functions, geographical units etc. The same action which we would excuse from someone in our team we suddenly find offensive or inappropriate from someone in another team.

Preventing and resolving conflicts: biases continued

Having biases does not mean we are always wrong. The driver in that car may well be a terrible driver, but our biases will lead us to think this is the case more often that it really is.

Sometimes just by knowing that we have these tendencies in our reasoning, we can react more calmly. So next time someone cuts you off in traffic, try to look for explanations that go beyond “what an idiot”, and you may feel yourself becoming less agitated than before.

But one of the most important steps to counteract bias is to ask questions that deliberately try to explore the views of the other person. Questions like: “How did the situation look like from your perspective?”, “Help me understand how you got to that conclusion”, “How would you have acted in my position?”, “What happened that you reacted this way?” can reduce the effects of bias. Sometimes, this can lead to conflicts being prevented before they even started, sometimes it leads to a better basis to resolve the underlying conflict.

Understanding conflicts: social needs introduced

But let’s assume you have verified that your biases have not led you to misjudge the situation and you still feel aggravated at the other person. Why is that? The answer is most likely that at least one of your primary social needs was threatened.

So what are those social needs and what happens to us if they were threatened? To answer the second question first: our bodies go into a (very physical) threat response.

Understanding conflicts – our biological threat response

The thing is that our body’s threat response has evolved a very, very long time ago, and hasn’t been updated since. And it has evolved to deal with very concrete, physical threats: like a lion jumping out at you in the savannah. Your body will quickly react to maximize your ability to fight, flight, freeze or fawn, while lowering any non-essential body systems.

That means pumping blood into your major muscles, enhancing your spatial perception, the mind races, increased heart rate, releasing adrenalin, increasing production of blood coagulation agents etc. At the same time, it turns down anything that takes up precious energy but would not help right now. For example, your digestive system slows down massively, your complex cognitive reasoning skills are reduced, creativity is reduced, we cannot focus for prolonged periods, etc.

While the threat response has not been updated, our threat detectors very much have. As humans evolved to form very complex social groups, our brains have evolved to detect a completely new source of threats: social threats. After all, being excluded from the group (or tribe) would have meant almost certain death within weeks or months for most of humanity’s time on earth.

As research has confirmed[1], our brains treat social threats in much the same way as they do physical threats, as anyone who has asked someone out on a date or had to hold a presentation can attest – heart racing, sweaty palms, fast and shallow breaths etc.

Clearly, that is not a helpful physical response to our modern workplace conflicts. You cannot just sprint out of the room during a stressful presentation or punch your boss after an unfair assessment, despite your body preparing you to do just that.

Understanding conflict – social needs explained

But to get back to the original question: what are those social needs? The SCARF model gives us five very concrete social needs, which can elicit the above-mentioned threat response.

S – Status – our relative importance to others

C – Certainty – the degree to which we (think we) can predict the future

A – Autonomy – our sense of control over events

R – Relatedness – a sense of safety with others, of friend rather than foe

F – Fairness – a perception of fair exchanges between people

Let’s take some examples, starting with status. Imagine you find yourself getting critical feedback by someone who you think has no right to do so – maybe because they have less expertise, are junior to you, only just joined etc. Status also explains why any kind of demotion is such a painful and exceedingly rare step.

For certainty, imagine your company is suddenly going through a big reorganisation, the ramifications of which are entirely unclear. Or a deadline is suddenly being shifted, or the requirements of a project.

Autonomy: imagine you are being micro-managed, have very limited scope for decision making etc.

Relatedness: imagine your team members do not accept you, maybe even exclude you or make jokes at your expense.

Fairness: imagine someone else being praised for your work, leaders not practicing what they preach, rules being applied unequally on a whim, etc.

Understanding conflict: social needs summarized

Our brains and bodies have evolved to respond to social threats the same way we react to physical threat. These needs are neatly summarized in the SCARF model (status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, fairness). So whenever we or others have one or more of these needs threatened, there is potential for conflict.

As a quick note: telling someone they are reacting irrationally in a conflict based on hurt social needs is like asking someone not to be hungry after not having eaten in a while. The systems that govern these reactions have evolved long before our higher reasoning skills and are not subject to our conscious control to the extent that we would sometimes like. Instead, it is more helpful to frame these autonomous reactions as pre-rational.

Resolving and preventing conflict: social needs

And just how we would resolve the issue of hunger by (eventually) satisfying the underlying need (i.e. eat something), conflicts caused by threatened social needs are best resolved by fulfilling the underlying social need.

So here are some suggestions for doing just that. Think of it like food for the social soul.

Status – positive feedback, public acknowledgment, recognition, promotions, higher level of responsibility, etc.

Certainty – making things predictable. Clear expectations, defining threshold levels for support or decisions, giving a time horizon, knowing what you need to do to get promoted, etc.

Autonomy – give people leeway to take decisions themselves, providing choices, empowerment, learning new skills, providing resources, etc.

Relatedness – being friendly, bonding with others, showing interest in someone’s hobby/family/life, team-building, sharing inside jokes, etc.

Fairness – Following up on promises, applying rules equally and fairly (also to yourself), transparent decisions, candidness.

It is important to note, that while we all share these needs, we are different in how much of each we need. One person may not need all that much relatedness, while their colleague very much does. And we differ in how to best satisfy those different needs. Status for one person may mean having a nicer desk, while praise from a respected expert may work better for the next person.

Of course these needs can interact with biases. Especially the egocentric bias can lead us to assume that whatever works well to satisfy a social need for us is also powerful for others.

To counteract this risk: 1) ask questions that help you better understand which needs are most important to someone, and how to satisfy those needs. 2) verbalise your own needs to make it easier for others to fulfil them.

Finally, not all these needs can be satisfied all the time, just like you will be hungry or thirsty from time to time. But by being mindful of these needs, by having vocabulary to talk about them and by trying to satisfy these needs, we may prevent plenty of conflicts or at least be quicker at identifying the underlying need(s) that lead to whatever conflict you’re having.

Notes:

[1] -Rock, D. (2008). SCARF: A brain-based model for collaborating with and influencing others. Neuroleadership Journal, 1, p1.

Turn theory into practice!

Discover our

Conflict Management

one-day masterclass and learn more about our offer.